In a few days, Senator Barack Obama will make his acceptance speech for the Democratic nomination to be President. Breaking recent precedent, he will make this speech not in the convention hall itself, but in an outdoor stadium, Denver's Invesco Field.

The last time the Democratic nominee for President gave his nomination acceptance speech in a large outdoor stadium was in 1960, when John F. Kennedy spoke at dusk in the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. It was another "change" election, and JFK was the youthful "change" candidate, opposed by the "experience" candidate, Richard Nixon.

In the previous two elections, the Democratic nominee had been Adlai Stevenson, whose speeches were intelligent and articulate, and who could make a case for the Democratic Party agenda. But though Stevenson engendered fierce loyalties in the party, he wasn’t exciting. He didn’t move large crowds. JFK knew that he could, and this event was the signal that he would in 1960.

So that’s the meta-lesson from JFK:

if you’ve got it, use it. While pundits and the hot air networks counsel Obama to reign in the rhetoric and stick to laundry lists of programs, there will be 80,000 or so people in the stadium ready to rock. They want to hear what 80,000 voices chanting “Yes, We Can!” sounds like. Obama got this far by inspiring people. If he’s going to win, he needs to motivate those who got him this far. They will help him spread the enthusiasm.

We want to hear him talk about change, about hope, about the fierce urgency of now. We want a little “Yes We Can.” Democrats should go home from Denver on fire.

Sure, the context of 2008 is different: the country was uneasy but pretty prosperous in 1960, Eisenhower was still a popular President so Nixon had advantages McCain doesn’t. But JFK was new. He was younger than Obama (though he had been in the House and Senate for 14 years.) After 7 years as VP, Nixon seemed to be a known quantity. Voters were unsure: change, or experience?

The race remained pretty even, even after the debates which historians—in retrospect—often say were decisive for JFK. But in that fall, the most obvious difference was that JFK’s crowds grew and grew, not only in size but in enthusiasm. Doubts were overcome by the contagion of hope. That’s what needs to happen this fall, particularly in October.

Then there are lessons from the speech itself…

Lesson #2: Become the leader of the party. JFK began his speech complimenting the party and the platform, and with a litany of other Democrats.

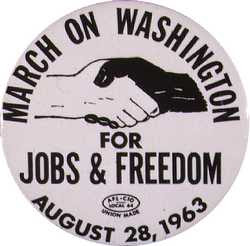

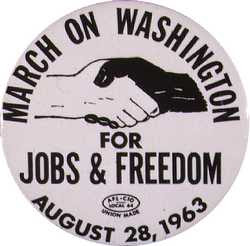

Lesson #3: Confront the elephant in the room. For JFK it was his Catholic faith. For Obama, it’s race. JFK devoted about 3 paragraphs to reassuring voters that he was independent, with his first allegiance to America. Obama is speaking on the 45h anniversary of Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream” speech. Obama was 2 years old. In large measure, he is a fulfillment of King’s dream, and he should own it. And he can do it within a larger context of America and the American dream.

Lesson #4: Go after the Republicans directly. JFK’s speech is remembered for introducing the “New Frontier.” (More about that coming up.) But he devoted five paragraphs in the middle of his speech to partisan rhetoric aimed at his opponent, Richard Nixon. For instance:

We know it will not be easy

to campaign against a man who has spoken and voted on every side of every issue.

JFK then drew the contrast between the parties in terms that ought to be familiar today:

But we're not merely running against Mr. Nixon. Our task is not merely one of itemizing Republican failures. Nor is that wholly necessary. For the families forced from the farm do not need to tell us of their plight. The unemployed miners and textile workers know that the decision is before them in November. The old people without medical care, the families without a decent home, the parents of children without a decent school: They all know that it's time for a change.Lesson #5: Focus on the future. That was really what distinguished JFK as a candidate, and it’s the natural move for the younger candidate to make (though in fact JFK was only 3 years younger than Nixon, and Nixon was a year younger than Obama is now.) JFK was influenced by Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. and his contrast of the Republicans as the party of the past and the Democrats as the party of the future. The Republicans practiced the politics of memory, he wrote in a book published a few years later, while the Democrats represent the Politics of Hope.

Here’s what JFK said:

Today our concern must be with that future. For the world is changing. The old era is ending. The old ways will not do.In this section of his speech, JFK sketched some of the challenges. While today scholars like to see him as a Cold Warrior, and he did talk about the need to engage Soviet expansion, he also emphasized the need for peaceful means.

The world has been close to war before, but now man, who's survived all previous threats to his existence, has taken into his mortal hands the power to exterminate his species seven times over.

He spoke briefly about domestic challenges, including Civil Rights:

A peaceful revolution for human rights, demanding an end to racial discrimination in all parts of our community life, has strained at the leashes imposed by a timid executive leadership.Then he reiterated the emphasis on change and the future:

It is time, in short for a new generation of leadership. ..The Republican nominee, of course, is a young man. But his approach is as old as McKinley. His party is the party of the past, the party of memory… Their pledge is to the status quo; and today there is no status quo.Lesson #6: Articulate a vision. This is the point in the speech where JFK begins talking about the New Frontier, and he does it by anchoring it in the moment, the time and place where he is speaking:

For I stand here tonight facing west on what was once the last frontier. From the lands that stretch three thousand miles behind us, the pioneers gave up their safety, their comfort and sometimes their lives to build our new West…

Some would say that those struggles are all over, that all the horizons have been explored, that all the battles have been won, that there is no longer an American frontier. But I trust that no one in this assemblage would agree with that sentiment; for the problems are not all solved and the battles are not all won; and we stand today on the edge of a New Frontier -- the frontier of the 1960's, the frontier of unknown opportunities and perils, the frontier of unfilled hopes and unfilled threats.

A little later he adds:

The New Frontier is here whether we seek it or not. Beyond that frontier are uncharted areas of science and space, unsolved problems of peace and war, unconquered problems of ignorance and prejudice, unanswered questions of poverty and surplus.Lesson #7: Include the audience, and ask not what you can do for them, but what they can do for their country: But the New Frontier of which I speak is not a set of promises. It is a set of challenges. It sums up not what I intend to offer to the American people, but what I intend to ask of them. It appeals to their pride -- It appeals to our pride, not our security. It holds out the promise of more sacrifice instead of more security.It would be easier to shrink from that new frontier, to look to the safe mediocrity of the past, to be lulled by good intentions and high rhetoric -- and those who prefer that course should not vote for me or the Democratic Party.

But I believe that the times require imagination and courage and perseverance. I'm asking each of you to be pioneers towards that New Frontier. My call is to the young in heart, regardless of age--to the stout in spirit, regardless of Party, to all who respond to the scriptural call: "Be strong and of a good courage; be not afraid, neither be [thou] dismayed."That is the choice our nation must make -- a choice that lies not merely between two men or two parties, but between the public interest and private comfort, between national greatness and national decline, between the fresh air of progress and the stale, dank atmosphere of "normalcy;" between dedication and mediocrity.All mankind waits upon our decision. A whole world looks to see what we shall do. And we cannot fail that trust. And we cannot fail to try.Give me your help and your hand and your voice.”

That last phrase would be one JFK repeated many times on the campaign trail—a call to participation in his campaign.

The acceptance speech will be the first and last time of the general election campaign that the candidate has the attention of a large chunk of the electorate at one time for an uninterrupted statement of this length.

But it’s more than speaking to millions of voters, many of whom are just beginning to focus on the election. Obama’s previous big speeches were in the context of a primary campaign, when he had to distinguish himself and his message from several other candidates, and when he had particular limits on what he said about his opponents within the Democratic Party.

Now Obama can do what JFK did, and draw a direct contrast between himself as the Democratic candidate, and McCain as the Republican candidate. He can define the choice voters have in November.

But he is also speaking to Democrats and the people who have been with him so far. He can motivate them to work for him, which is especially important this year, for Obama needs highly motivated voters in several core groups, and enthusiastic volunteers to put the ground game in motion.

JFK managed to do both. Obama can, too. JFK inspired me, at 14 years old, to work for his campaign. His acceptance speech—which I recorded on our reel-to-reel tape recorder, and played for my social studies class—was a big reason why.